FILM STUDIES – Salaam Cinema! An Introduction to Film in Iran by Sara Saljoughi

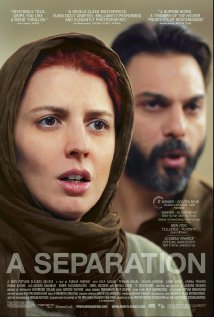

Iranian art cinema received a warm global welcome in the 1980s and 90s with the success of films by directors such as Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and Bahram Beyzai. More recently, Asghar Farhadi’s Academy Award winning film, Jodai-e Nader az Simin/A Separation (2011), has once again put Iranian cinema in the global spotlight. However, outside Iran, surprisingly little is known about the country’s rich cinematic culture, which began with the advent of the moving image. This article provides a short introduction to that history, with a special emphasis on experimental and art cinema and women’s participation in the film industry both before and after the 1979 revolution.

Asghar Farhadi

Cinema in Iran begins in 1900. This year marks both the production of the first “Iranian” film – a travelogue made in Belgium by Ebrahim Khan Akkasbashi Sani al-Saltaneh, a photographer of the Qajar court – as well as the official opening of the country’s first public cinema, Soleil Cinema, in the northwestern city of Tabriz. Shortly thereafter, in 1904, Cheraq Gaz Street Cinema, the first commercial cinema, was opened. From its earliest emergence, cinema’s reception and circulation in Iran prompted questions about its suitability, that is, cinema’s potential to disrupt and offend existing cultural and social practices. Film was largely understood as an imported medium until the 1980s and 1990s when Iranian cultural institutions, such as the Farabi Film Foundation, began to promote the idea of a homegrown, local cinematic tradition boasting its own auteurs and the growth of a canon. Thus for long cinema’s role in Iranian society functioned both as a symbol of an invading modernity but also, in the mid-twentieth century, as part of the broader machinery of Mohammad Reza Shah’s modernization program.

1931 saw the release of what can be called Iran’s first silent feature-length film, Abi and Rabi, a slapstick comedy directed by Ovanes Ohanians, a Russian-Armenian immigrant who also opened Iran’s first film studio (Perse Film Studio) and first film acting school (Parvareshgah-e Artisti-ye Sinema). Ohanians and Perse Film Studio also produced Haji Agha, Aktor-e Sinema/Haji Agha, the Movie Actor (1933). This film is a sharp reflection on the role of cinema in what is often deemed Iran’s longstanding tension between tradition and modernity. Haji Agha offers a particularly powerful critique of a society that is unable to see itself: despite attempts to introduce the most modern technologies (in this case the institution of cinema), the society remains closed and reticent about the reach of such technologies. In the film, a director (played by Ohanians) is searching for a subject for his film, when he receives a suggestion to film Haji Agha, a wealthy conservative man. Haji’s daughter, son-in-law, and servant help the director orchestrate a series of events that enable the director to film Haji in action. When the film is finished and Haji views it, he sees his own image on the screen and, enthralled by it, begins to appreciate the merits of cinema. These two important films, Abi and Rabi and Haji Agha, the Movie Actor, point to the multi-ethnic and in a sense transnational origins of Iran’s “national” cinema. This trend continues with the first Iranian talkie, Dokhtar-e Lor/The Lor Girl (1933), which was filmed in India and directed by Abdolhossein Sepanta. The Lor Girl was also the first Iranian film in which a Muslim Iranian woman (Rouhangiz Saminejad in the lead role) was cast. Until this point, Armenian and/or Christian Iranian women performed in the few instances where women were represented on screen.

In the mid-twentieth-century, a domestic, commercial cinema (often referred to as filmfarsi, or films made in the Persian (Farsi) language), resulted in the production of historical films, melodramas, thrillers, and a genre unique to Iran known as Jaheli or kolah makhmali (velvet hat), which depicted a crudely represented male chauvinism. Critics have debated whether filmfarsi can be considered a genre in and of itself or whether the term is a convenient euphemism used to contrast the domestic film industry with what was considered the “superior” foreign equivalent in the West. The films that fall under the rubric of filmfarsi tend to be ignored or devalued for their perceived vulgarity and maintenance of the status quo. And yet despite these shortcomings, it would be hard to contest the notion that filmfarsi played a pivotal role in shaping the widespread antagonism toward cinema that was a large part of the revolts leading to the 1979 Iranian Revolution. This particular reaction to filmfarsi – that its films ought to be ridiculed and resisted – had in part to do with the representation of women. Filmfarsi established a star system that featured women in a set of representations that became the dominant norm. The representations of women reflect a synthesis of imported ideology and domestic cultural norms, and emerge from the formal and narrative structures of melodrama, particularly in its simplistic rendering of “good versus evil.” Women appeared in the form of stock characters with little nuance or complexity, and were often portrayed as singers and dancers in nightclubs, cafés, and restaurants. Women’s performances were filmed from a heterosexual male point of view, a method that strived to imitate the gaze of Hollywood cinema.

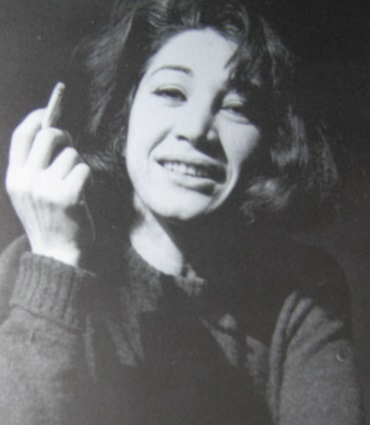

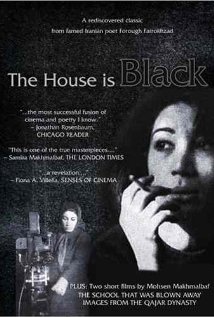

In Nader T. Homayoun’s excellent 2007 documentary, Iran: Une revolution cinématographique/Iran: A Cinematic Revolution, there is distinct emphasis placed on the extraordinary and surprising shift in Iranian cinematic culture that happened after the 1979 revolution. How was it that a society so enraged by cinema’s encroachment – as an arm of the Western culture industry – turned, in the span of a few years, into a nation of cinephiles, with government agencies stating that there should be at least one Iranian film at every international film festival? Part of the story of this shift is rarely told or studied with nuance. Roughly seventeen years prior to the Revolution, another film movement began in Iran – Mowj-e No/[Iranian] New Wave – that, despite being cut short by the events of the revolution, was actually in many ways prophetic of the revolution. In addition to voicing the myriad heterogeneous concerns that generated the antagonism necessary for the Revolution to happen, the New Wave films both responded to and generated an interest, however small and marginal, for different kinds of images than those offered by filmfarsi. Although it is not always considered a cohesive or self-identified movement, what is now called the “Iranian New Wave” began in 1962 with the late poet Forough Farrokhzad’s experimental documentary, Khaneh Siah Ast/The House is Black. Since its release, the film has defied the various categories within which critics and scholars have attempted to contain it: poetic realism, educational documentary, institutional documentary, experimental cinema, and so on. Made by the most important female poet working in the Persian language, The House is Black uses the site of a leper colony to stage a meditation on visuality, community, and the subjective voice. Although it was the only film she directed, Farrokhzad drew on her poetry practice (also noted for its use of the subjective) to develop images through an innovative use of montage combined with her voiceover reading passages from the Quran and the Hebrew Bible, resulting in a new cinematic language that has continued to be influential on Iranian filmmakers. In fact, Farrokhzad was the first Iranian filmmaker to use the formal techniques that would later be recognized as hallmarks of the post-revolutionary “New Iranian Cinema”: location shooting; the use of non-professional actors, with an emphasis on children; the interplay between non-fiction and fiction forms; the incorporation of poetry. Although The House is Black is widely recognized as an important film (it continues to find new audiences, such as its recent inclusion in an exhibition on the essay film at the British Film Institute), it has suffered from attempts to make it “fit” into the genre of documentary, rather than being celebrated for providing the future of Iranian art cinema with such experimental origins.

Forough Farrokhzad

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, the Iranian New Wave flourished in terms of developing a mode of committed cinema heavily influenced by Italian neorealism. Some of the finest examples of these works include Kamran Shirdel’s documentaries of urban life: Nedamatgah/Women’s Prison (1965); Qa’leh/Women’s Quarter (1965-1980); Tehran is the Capital of Iran (1966-80); Oun Shab Ke Baran Oumad/The Night It Rained (1967-1974). Shirdel’s documentaries were strong challenges to the Pahlavi monarchy’s desire to present Iran as a modernized and wealthy country. These films, along with works by Massoud Kimiai, Nasser Taghvai, and Sohrab Shahid Saless, among several others, presented a new kind of image: wrung from reality, laid bare, and an invitation to see anew. It is important to note too, that the filmmakers of the New Wave were highly concerned with formal innovation (see for example, Ferydoun Rahnema’s films, particularly Pesar-e Iran az Madarash Bikhabar Ast/The Son of Iran Has No News From His Mother (1976)), and so their attempts at realism often involved thinking about constructing a kind of realistic film image by juxtaposing the content of political struggle with innovative techniques in form. Furthermore, many of the New Wave filmmakers completed part of their formal training abroad in the United Kingdom, France, and Italy, and thus saw themselves as part of a broader global conversation on the relationship between aesthetics and politics.

On August 19th, 1978, the Cinema Rex in the city of Abadan was set to fire and burned to the ground during a screening of Massoud Kimiai’s controversial film Gavaznha/The Deer (1976). The film had 700 spectators, which is in and of itself a notable number, and the reports of the event vary, citing 377 deaths or 600 deaths.[1] This event is often cited as one of the crucial pre-revolutionary moments in the very long year of 1978. Given that the fire happened in Abadan, a town in southwestern Iran that is home to one of the largest oil refineries in the world, it provoked massive protests by oil workers who joined the various anti-Shah movements in large numbers following this event. The burning of the Cinema Rex would turn out to be the most significant of many movie theatres set to fire over the next two years. Cinema Rex’s location in Abadan is important for the way that it brings together the frustrations of Iran’s working classes with the building anti-Western sentiment of the burgeoning Islamic movement. The Cinema Rex fire prompted many copycat fires that resulted in 180 destroyed cinemas by 1979. Cinema, and specifically, films and the foreign cultures often imported with them, was seen as one of the sources for the degradation of Iranian culture. Following the Revolution, the importing and exhibition of foreign films stopped completely. For several years, the production, distribution, and exhibition of domestic films also grinded to a halt. It seemed that cinema was inextricable from the diseased and impoverished state of the nation during Mohammad Reza Shah’s reign (1941-1979).

The cinema that emerged after several years of non-production became what is often referred to as the “New Iranian Cinema.” The sudden renewal of Iranian cinema is in part due to the late Ayatollah Khomeini, who upon seeing Dariush Mehrjui’s New Wave classic, Gav/The Cow (1969), declared that Iran needed more films like it. It was not the cinema itself that the leaders of the newly established Islamic Republic of Iran opposed, but the degraded and imitative cinema that had for so long dominated Iranian screens. In fact, the Islamic Republic valued cinema’s ability to speak to Iranians at multiple registers, and the government seized on that ability throughout the 1980s, particularly during the Iran-Iraq war, which in many respects was buttressed by a thriving war film industry. Cinema seemed to present a clear trajectory: by shaping the ideal spectator, it was possible to shape the ideal citizen.

With the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran came a set of new regulations and requirements for representation. For example, given that Iranian women were now required to adhere to mandatory veiling regulations, so it followed that women must be represented on screen in a hejab, even if the diegetic space of the film was a private one such as the home, i.e., not a space in which a woman would normally wear a hejab. Another example of the new guidelines on representation is the representation of interaction between members of the opposite sex. Because women and men could not, for example, embrace on screen, many early post-revolutionary films lack the kind of realist nuance that pre-revolutionary art films were trying to attain. With these new guidelines and limits on representation, there was a concerted effort to transform the dominant (and sexualized) heterosexual male gaze into what was described as a “sisterly look” at women. Many film critics have argued that the dominance of storylines built around children in post-revolutionary Iranian cinema is precisely due to these stifling censorship laws. Instead of trying to work around the guidelines, filmmakers avoided anything that could get cut or edited out by the censors. In addition to making films centered on child characters, many directors worked with screenplays that completely excluded either men or women. For example, Rakhshan Bani-Etemad’s Banu-ye Ordibehesht/The May Lady (1999) is an epistolary romance in which the male love interest is not physically present.

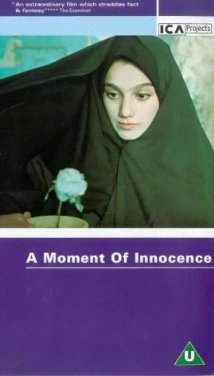

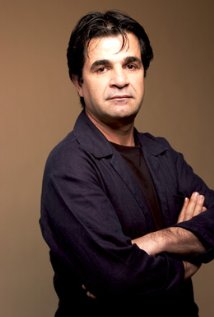

From the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, Iranian art films were a fixture at international film festivals, where they gained wide acclaim. Films by Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and Bahram Beyzai, and Rakhshan Bani-Etemad, to name a few of the first and most widely recognized names, were noted by critics for their originality and poeticism. These films, such as Bashu, the Little Stranger (1986), Where is the Friend’s Home? (1987), Close-Up (1990), Nargess (1992), and A Moment of Innocence (1995), among countless others, often told narratives about everyday experiences and struggles, and were almost always cast with non-professional actors. Many of the films (especially those in Kiarostami’s “Koker Trilogy”) exhibited stunning landscapes and images of rural life in Iran and thus were far removed from dominant representations of Iran that circulated in the West throughout the 1980s and 90s. Some films (such as Close-Up and Samira Makhmalbaf’s The Apple) played with the fusion of documentary and fiction. In a sense these films, and especially their global reception, speak to a desire for so-called authentic narratives from Iran at a historical moment in which the country was demonized. Through cinema, people across the world gained access to a different mode of representation – one that came from within Iran and spoke to film audiences.

Mohsen Makhmalbaf

While serious fans of global cinema know how Iranian cinema evolved following the Revolution, many outside the country are not aware of the remarkable role women have played in that process. Prior to the 1979 Revolution, there were only a (small) handful of films made by women – most notably Farrokhzad’s The House is Black and Marva Nabil’s remarkable The Sealed Soil (1977). Following the Revolution (and a few years after the brief period of stagnation), women filmmakers as diverse as Tahmineh Milani, Rakhshan Bani-Etemad, Marziyeh Meshkini, Niki Karimi, and Samira Makhmalbaf, among many others, emerged in a creative atmosphere that, despite its restrictions, had no precedents in the history of Iranian cinema.

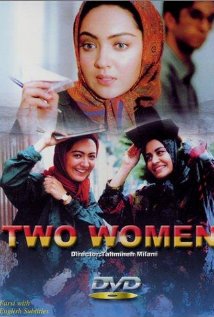

The two most prominent women filmmakers following the revolution, Rakhshan Bani-Etemad and Tahmineh Milani explicitly address women’s issues in their films. They also happen to be two of the most widely acclaimed filmmakers in Iran, regardless of gender. Bani-Etemad’s film Nargess won first prize at Iran’s Fajr Film Festival in 1992, marking the first time a woman had won this prize. The international film community has recognized both filmmakers for their work. Milani’s films are more radical in their position on women’s issues, with Two Women (1999) being a particularly compelling work. Other women filmmakers working in Iran have critiqued the state and social life after the revolution without necessarily identifying their work as belonging to something like “women’s cinema.” One of the most provocative films of the post-revolutionary era was Samira Makhmalbaf’s documentary-cum-feature film Sib/The Apple (1998). The film portrayed the life of two young girls whose parents had kept them in isolation in their home since their birth. Like Kiarostami in 1990’s Nema-ye Nazdik/Close-Up, Makhmalbaf enlisted the actual family to play themselves in the documentary about their lives. Marziyeh Meshkini’s Roozi ke zan shodam/The Day I Became a Woman (2000) is a film that experiments with narrative structure in order to think about time, motion, and the process of “becoming woman.”

Tahmineh Milani

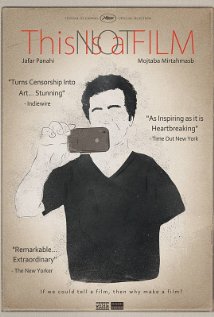

One of the long-term social effects of the 1979 revolution has been the massive and ongoing emigration of Iranians, and especially of artists and intellectuals. To speak today of an “Iranian cinema” is also to speak of the variety of filmmakers who live beyond Iran’s borders but continue, in their work, to engage either explicitly or implicitly with questions of the nation. Among the well-known diasporic filmmakers are Bahman Ghobadi (Turtles Can Fly; A Time for Drunken Horses; No One Knows About Persian Cats), Ziba Mir-Hosseini (Divorce Iranian-Style, made in collaboration with Kim Longinotto); and Marjane Satrapi (Persepolis; Chicken With Plums, both collaborations with Vincent Paronnaud). Sohrab Shahid Saless, one of the most important New Wave filmmakers in the 1970s who lived in exile following the Revolution, continued his career in the former West Germany, where he made films such as1983’s Utopia, among others. Video artist Shirin Neshat’s adaptation of Shahrnush Parsipur’s 1990 novella Zanan bedoone Mardan/Women without Men won the Silver Lion for best directing at the Venice Film Festival in 2009. In 2010, the filmmaker Jafar Panahi (The Mirror, 1997; Crimson Gold, 2003; Offside, 2006; This is Not a Film, 2011; Closed Curtain, 2013, among others) was arrested for his support of 2009’s Green Movement as well as for various other unverified allegations. Following his imprisonment, and subsequent release, from Tehran’s Evin Prison, Pahani was officially banned from making films for 20 years, a ruling that sparked a large international protest headed by major players in the global community. However, Panahi has made two films since that time, including This is Not a Film, which was made while he was under house arrest. Iranian cinema has been in the news more recently with the success of Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation. In an interesting move from the government of the newly elected Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, Iran has selected Farhadi’s Le Passé/The Past (2013) as its official entry for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. Some conservatives officials have criticized the choice, arguing that the film is made in France and filmed almost entirely in the French language, while others see it as indicative of a cultural “thaw,” indicating, once again, a renewed relationship with the West. However, from its outset, Iranian cinema has been transnational, a tendency that does not seem to be waning.

Jafar Panahi

Highlights of Iranian Cinema

The list below is a suggested viewing list. It is by no means a complete list of Iranian films, nor should it be understood as a “best of.” Rather, it gives those new to Iranian cinema the chance to see films from different moments in Iran’s cinematic history, with each film offering a different part of the larger story.

Yek Atash, 1961, dir. Ebrahim Golestan

The House is Black, 1962, dir. Forough Farrokhzad

Mudbrick and Mirror, 1965, dir. Ebrahim Golestan

Siavash at Persepolis, 1967, dir. Ferydoun Rahnema

Qeysar, 1969, Massoud Kimiai

The Cow, 1969, dir. Dariush Mehrjui

P Like Pelican, 1972, dir. Parviz Kimiavi

Tranquility in the Presence of Others, 1973, Nasser Taghvai

A Simple Event, 1973, dir. Sohrab Shahid Saless

The Sealed Soil, 1977, dir. Marva Nabil

The Runner, 1985, dir. Amir Naderi

Where is the Friend’s Home, 1987, dir. Abbas Kiarostami

Bashu, the Little Stranger, 1990 dir. Bahram Beyzai

Close-Up, 1990, dir. Abbas Kiarostami

Narges, 1992, dir. Rakhshan Bani-Etemad

A Moment of Innocence, 1995, dir. Mohsen Makhmalbaf

Taste of Cherry, 1997, dir. Abbas Kiarostami,

The Mirror, 1997, dir. Jafar Panahi

The Apple, 1998, dir. Samira Makhmalbaf

Two Women, 1999, dir. Tahmineh Milani

Ten, 2000, dir. Abbas Kiarostami

Iran: A Cinematic Revolution, 2007, dir. Nader T. Homayoun

Turtles Can Fly, 2004, dir. Bahman Ghobadi

About Elly, 2009, dir. Asghar Farhadi

A Separation, 2011, dir. Asghar Farhadi

Here Without Me, 2011, dir. Bahram Tavakoli

[1] Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 3: The Islamicate Period, 1978-1984 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012): 2.